Riding the SURF to shark research

RI’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fund (SURF) led Seton Smith ’26 to work with the Atlantic Shark Institute.

For Seton Smith ’26, the path to studying sharks in the deep sea didn’t begin with a carefully mapped plan – it began with a campus visit that simply felt like home.

Originally from New Jersey, Smith knew she wanted to study biology in New England and was especially drawn to marine science. Salve Regina University wasn’t initially on her radar, but after a last-minute campus tour during a college road trip, everything changed.

“As soon as we got here, it just felt right,” Smith said. “The campus is beautiful, but it was more than that. The people were so welcoming, and I immediately felt like I could be here for years and be happy.”

Now a biology major with an environmental science concentration, Smith has transformed that early sense of belonging into a series of hands-on research opportunities – each building on the last – thanks in large part to Salve’s close-knit academic community and its emphasis on undergraduate research.

Mentoring, networking and internships

Smith’s entry into marine research began the summer after her sophomore year through the Summer Undergraduate Research Fund (SURF) program. Designed to connect students across Rhode Island colleges with faculty mentors whose research aligns with their interests, SURF opened a door Smith hadn’t known existed.

Through the program, Smith was matched with the Davies Lab at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography (URIGSO), where she worked under Ph.D. candidate Christine de Silva on a marine ecology project focused on sharks.

“It allowed me to work with a researcher who was studying exactly what I was interested in, even though that work wasn’t happening directly at Salve.”

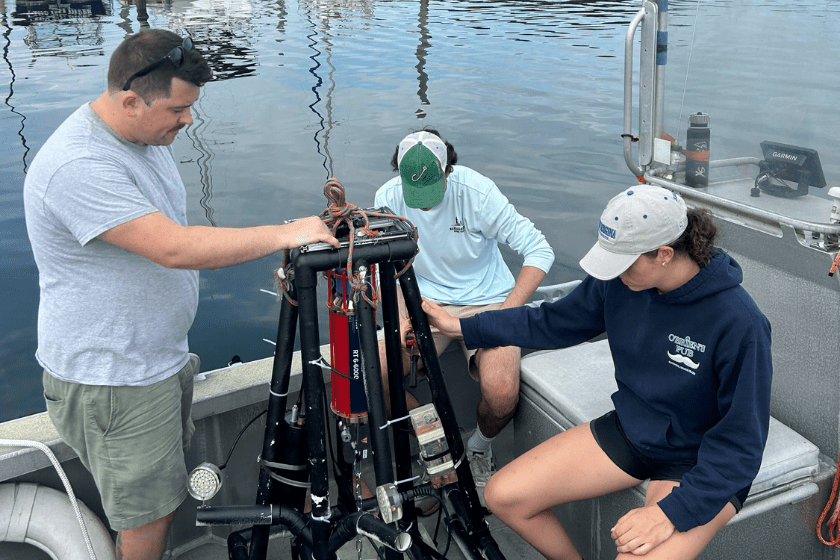

Her role evolved quickly. What began as assisting with the design and construction of a baited remote underwater video system, also known as a BRUV, soon expanded into field deployment, footage analysis and long-term data annotation. The system was eventually deployed as far as Georges Bank, nearly 100 miles offshore, capturing more than 13 hours of deep-sea footage at a time.

“We saw dog fish, chain catsharks, different types of skates and lots of other fish as well,” shared Smith. “Since we’re focusing on sharks, we make note of everything, but really analyze how the sharks act, and analyze the footage for any patterns we notice.”

As Smith reviewed the recordings, she documented species interactions, patterns of movement and environmental changes over time, contributing to a broader effort to understand shark behavior and improve research efficiency through emerging tools like artificial intelligence (AI).

“A huge part of this project is developing an AI model that we can analyze and annotate data with. We are exploring how much more efficient it could be, how much faster, but are taking into account if we’ll be losing quality in the process.”

That work soon led Smith beyond the lab and into collaboration with the Atlantic Shark Institute, where de Silva was also affiliated. Through the partnership, Smith assisted with BRUV deployments and data analysis at multiple sites, including waters around Block Island and Cape Cod.

“It became this really interconnected web,” Smith said. “I met one person, who introduced me to someone else, and that led to another amazing opportunity.”

Those connections even brought Smith into the orbit of documentary filmmaking, as she crossed paths with nature filmmaker Tomas Koeck while assisting with field research for the short documentary “Chasing Fins,” spotlighting the institute’s work.

Across multiple semesters and summers, Smith worked with the Atlantic Shark Institute through her formal internships with the URIGSO before transitioning into a volunteer role with the institute this year, choosing to remain involved because of the relationships and long-term impact of the research.

Beyond the lab

While Smith’s research sharpened her technical skills, it also exposed her to another essential side of scientific work: grant writing.

During the spring of her junior year, Smith worked closely with Dr. Belinda Barbagallo, associate professor and chair of the biology department, to develop a pre-doctoral grant proposal modeled on the National Science Foundation application process.

“It was eye-opening,” Smith said. “You see all these incredible research projects, but they don’t happen without funding. Learning how to build a project, justify it and explain why it matters was huge.”

The experience challenged her to blend two very different writing styles – technical precision and personal vision – while learning how scientists plan for uncertainty by designing projects with multiple goals and safeguards.

“That process completely changed how I think about research,” she said. “Failure is part of science, but you learn how to pivot and keep moving forward.”

That foundation proved invaluable when Smith began applying for the Fulbright Program, proposing a research project that would take her halfway around the world.

While reviewing literature related to BRUV design, Smith became deeply interested in the work of an Australian researcher whose papers shaped her own thinking about underwater survey methods. On a leap of faith, she sent a cold email – one that resulted in a Zoom call, a proposed collaboration and a letter of affiliation.

Smith’s Fulbright application centers on research at Deakin University in Victoria, Australia, where she would use BRUV surveys to monitor artificial reef development and help design a long-term plan for tracking reef recovery over the next decade.

“It all came full circle,” Smith said. “The grant writing experience, the research at URI and the Atlantic Shark Institute – it was everything I had been practicing.”

She is currently awaiting the results of her application.

Prepared and supported

Throughout her journey, Smith credits Salve’s biology program and faculty with giving her both the confidence and the flexibility to pursue ambitious opportunities.

From small lab sections that foster collaboration to professors who encourage students to explore beyond the classroom, Smith says the University’s supportive environment made it easier to take risks and ask questions.

“I’ve learned how to transfer skills from class to research and from research back into class,” she said. “I don’t panic when things go wrong anymore. I think about the purpose, how to adjust and how to move forward.”

That mindset, she says, reflects Salve itself.

“It’s small, but nobody falls through the cracks,” Smith said. “People remember you. They look out for you. And that’s what has made all the difference.”