A tyrannical piano teacher, world peace and migratory birds walk into a library…

McKillop Library’s spring faculty lecture series proves scholarship can be surprisingly fun.

If you’ve ever wandered into McKillop Library on a late afternoon and heard laughter drifting down from the atrium – followed by a deeply thoughtful question about geopolitics, music or migratory birds – you’ve likely stumbled onto one of Salve Regina University’s quiet traditions.

For Dawn Emsellem-Wichowski, director of library services, that’s exactly the point.

Each semester, the library curates its faculty lecture series by keeping close tabs on what professors are researching, especially those returning from sabbatical, and by listening in while librarians teach information-literacy sessions in classes or notice a newly published book. The goal, she said, is simple but ambitious: give the Salve community a window into all kinds of scholarship.

"I’ve loved learning how research is conducted in different disciplines, how experts in the humanities, sciences and social sciences develop questions, what constitutes evidence and why they think their research is important," said Emsellem-Wichowski.

This spring’s lineup stretches that idea in every direction – from a surreal 1950s children’s musical to global peacebuilding to the wetlands and coastlines of Aquidneck Island. And fittingly, it all begins with a piano… that has 5,000 fingers.

A Cold War musical fever dream

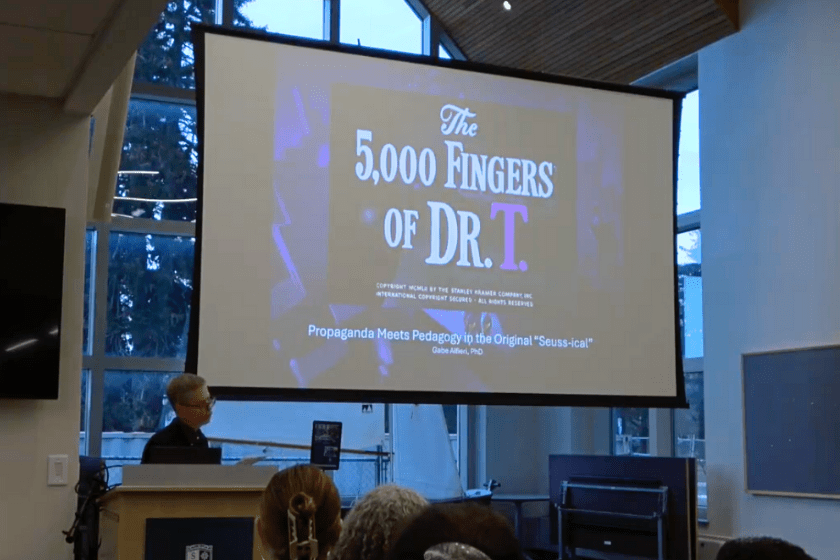

The setup to the spring’s opening lecture asks: What do Dr. Seuss, the Cold War and music theory have in common?

According to adjunct music professor Dr. Gabe Alfieri, quite a lot.

His talk, "The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T: Cold War Propaganda Meets Music Pedagogy in the Original ‘Seuss-ical’," explored the 1953 children’s film "The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T," a little-known musical written and designed by Dr. Seuss. Beneath its colorful sets and absurd humor lies a surprisingly layered cultural artifact.

The film, scored by German-Jewish émigré composer Friedrich Hollaender, who fled Nazi Germany, contains 15 original songs touching on capitalism, childhood, gender and postwar family life. In typical Seussian fashion, the story unfolds in a dream world where a tyrannical piano teacher forces children to practice on a gigantic keyboard requiring 5,000 fingers.

But Alfieri explained that the exaggerated premise isn’t random. The piano itself becomes a symbol of mid-century anxieties: authority versus freedom, masculinity versus femininity and the tension between adults and children. Unlike other Cold War musicals where music resists fascism, here music enforces an absurd authoritarian regime – until chaos and sound itself overthrow it.

In other words, the strangest children’s movie many people have never seen turns out to be a commentary on politics, education and family structure in post-World War II America.

Alfieri, whose research focuses on American theater and film music and what he calls "vocal polystylism," has presented nationally and published in journals including American Music and the Journal of Singing. But for this audience, the appeal was immediate: you didn’t need to know music theory to enjoy realizing that a whimsical musical might also be a cultural time capsule.

Rethinking peacekeeping

On Feb. 19, the conversation shifts from imaginary dictators to very real conflicts.

Political scientist Dr. Yvan Ilunga’s lecture, "Avoiding the Chaos: Rationality of Preventive Measures for Lasting Peace," will ask a deceptively simple question: Why do some conflicts return even after peacekeeping missions?

Ilunga points to international efforts since 1945, especially through the United Nations, that have reduced wars between countries but struggled to address instability within them. The missing piece, he argues, is often basic human needs.

"While these measures have been effective in reducing interstate conflicts, they have not adequately addressed internal fragility often resulting from unmet basic human and societal needs, such as those related to education, health, public safety and justice," said Ilunga.

Rather than sending troops after crises erupt, he advocates preventive measures focused on strengthening communities. He calls this approach "peace recovery" – building resilient societies centered on human well-being rather than just restoring political institutions.

His hope for attendees is that they leave with a new perspective: global peace begins locally.

An associate director of the master's in international relations and assistant professor who teaches at the undergraduate, master’s and doctoral levels, Ilunga researches humanitarian action, civil-military interaction and conflict in Africa. He is also the author of "Humanitarianism and Security: Trouble and Hope at the Heart of Africa" and speaks four languages – English, French, Swahili and Lingala. Yet the takeaway of his lecture is accessible: sustainable peace is built not only through diplomacy, but through functioning communities.

Birds, climate and the next decade of research

In March, the series moves outdoors – at least conceptually.

Biologist Dr. Jameson Chace’s Mar. 26 lecture, "Tacking! New Directions in Ecological Research and Teaching," grows directly out of his recent sabbatical year, which he used to reflect on past research and chart the next 10 years of his work with students in mind. During that time, he:

- Analyzed a decade of migratory bird banding data

- Studied five summers of songbird nesting success on Rose Island and mainland Middletown

- Learned to record bird songs and bat echolocation

- Developed mapping skills using GIS

- Helped launch conservation education with the Norman Bird Sanctuary

- Volunteered aboard NOAA’s research vessel Bigelow counting seabirds

- Began writing a natural history book about Rhode Island

Why does it matter? "That’s easy," said Chace. "The sixth mass extinction."

Scientists warn that many species worldwide are declining at unprecedented rates, and birds are often early indicators of broader environmental change. By studying migration patterns, nesting success and habitat quality on Aquidneck Island, Chace’s work helps researchers understand how climate change and habitat loss affect wildlife – and what local conservation efforts can do to slow those trends.

A professor and chair of the Department of Cultural, Environmental and Global Studies, Chace focuses much of his research on creating field opportunities for undergraduates. He has received two National Science Foundation RI-EPSCoR grants and spends much of his time studying birds and coastal ecosystems across Aquidneck Island and Narragansett Bay.

Why the lectures matter

For Emsellem-Wichowski, the real highlight of the faculty series isn’t just the presentations; it’s what happens afterward.

"As much as I enjoy hearing experts discuss their research, it’s always interesting to hear what piques the interest of the students, faculty and staff who are in attendance," shared Emsellem-Wichowski. "Often the presenter will be floored for a second, while they consider the implications of the question."

Over the years, she’s noticed that audiences ask questions they might never raise in a classroom: a biology major curious about music, an English student asking about peacekeeping or a business student suddenly interested in wetlands ecology. Attending research talks across disciplines, she said, reveals how scholars ask questions and why they care about the answers.