Dr. Jameson Chace joins NOAA research voyage exploring the Northwest Atlantic

On May 27, Dr. Jameson Chace, professor and chair of the Department of Cultural, Environmental and Global Studies at Salve Regina University, boarded the research vessel Henry Bigelow. He joined a research team from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as a volunteer to help monitor and explore marine resources and oceanographic conditions in the Gulf of Maine and the Northwest Atlantic.

The voyage was part of a monitoring and analysis project spanning more than four decades that informs local and international fisheries management, protected species research and climate science. We caught up with Chace to learn more about the trip upon his return June 6.

Q: How did you get involved in this research voyage?

A: NOAA senior research biologist Harvey Walsh and contract biologist Allison Black invited me to join.

Q: How many people were on the trip/boat and generally what were they doing?

A: There were about 30 of us on the 208-foot boat, the Bigelow -- five deck crew members, five engineers, seven NOAA officers and 11 researchers. The researchers worked in crews of six or so, in 12-hour shifts, which were from 3 a.m. to 3 p.m. and 3 p.m. to 3 a.m. The group included Harvey Walsh, two group leaders, two undergraduate volunteers, two graduate students, four research biologists from the University of Connecticut and University of Rhode Island, two NOAA technical specialists and two whale/seabird observers – Allison Black and me.

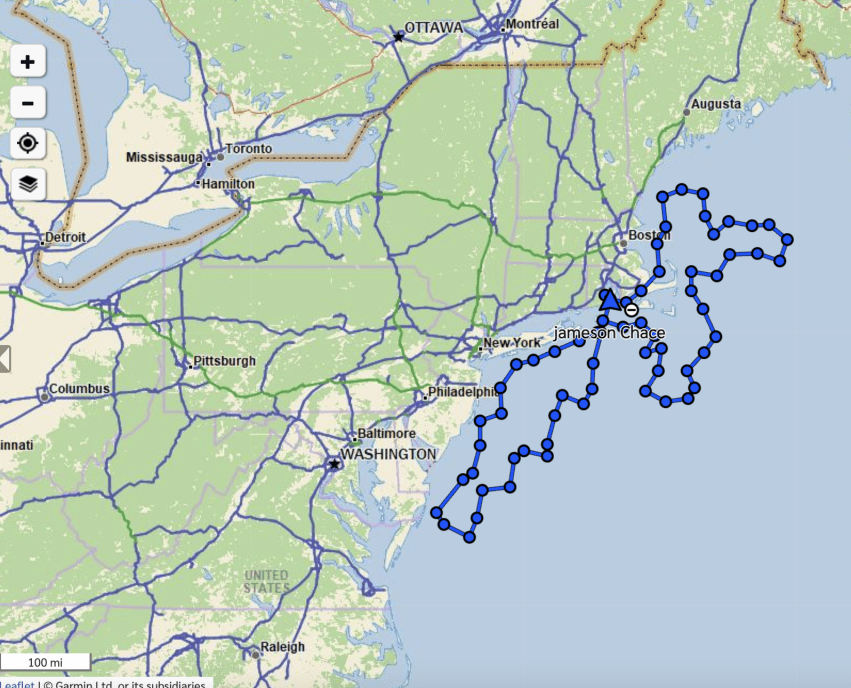

The larger program is called ECOMON, short for ecological monitoring. Voyages for the Northeast region move between the Gulf of Maine and Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, covering all offshore waters, conducting water physical chemistry sampling CTD (conductivity, temperature and depth) at each of 83 ECOMON stations once per season. NOAA has been doing this since the 1970s. The stations are not marked; they are GPS locations usually along the continental shelf.

In terms of what everyone was doing, there’s a great explanation on the NOAA website: “Seawater conducts electricity. This conductivity varies with the amount of dissolved salts in the ocean, and scientists use it to estimate the salinity of seawater. The combination of temperature and salinity at various depths helps define marine habitat boundaries, track ocean circulation and monitor changes in climate. This can help explain changes in marine species distribution and productivity.”

Researchers also sample phytoplankton in “bongos” at each station, which are vertical samples from the bottom to the surface. They attach fine-mesh nets to adjoined steel rings which help them collect zooplankton, phytoplankton, larval fish, fish eggs and the planktonic larval stages of a wide range of marine life. They use samples from this survey to update indices of plankton abundance used in environmental assessments.

Additionally, vertical water samples were collected for later analysis. For this, they dropped a cylinder of tubes to the bottom, opened depths tubes to collect water at specific depth and then closed them, raised to the next level, etc. One group on the ship was measuring mercury levels.

Allison Black and I were aboard to watch for and record any seabirds, marine mammals and sea turtles we encountered along the cruise track. We typically moved about 8 to 10 knots. We counted all species encountered within 300 meters of the ship and noted, whenever possible, any that were outside of 300 meters.

Q: What was your role?

A: My role was to assist Allison Black in counting whales and seabirds during all daylight hours, when visual conditions were good. This work falls under the Atlantic Marine Assessment Program for Protected Species. The program is a partnership among scientists from NOAA, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and the U.S. Navy.

Q: What were some of the highlights of the trip for you?

A: Birds and whales – many of which I had never seen before, because I have never ventured this far offshore for so long. Common dolphins and Atlantic white-sided dolphins were new to me, as were 10 different species of seabirds. Seeing feeding eruptions of hundreds of birds, hundreds of dolphins and whales -- minke, humpback and fin were spectacular.

As an ornithologist, I had a chance to see birds that I almost never get to see, including over 1,200 Wilson’s storm-petrels, small birds that fly like butterflies across the ocean eating zooplankton. They breed in Antarctica and yet span the globe across all the oceans. I added to my life-list of birds: Leach’s storm-petrel, South Polar skua, parasitic and long-tailed Jaeger, great, Manx and Cory’s shearwaters. I counted 1,384 sooty shearwaters, 361 great shearwaters, 581 Cory’s shearwaters and six Manx shearwaters – all open-water ocean birds that return to oceanic islands to breed.

There were also a number of land birds that found a resting spot on the boat – Darwinian evolution at work for many of them, but perhaps a lucky few would survive overwater movement to colonize new places. How often does this happen? Apparently quite often. We encountered four different warbler species, cedar waxwing, some swallows and a chimney swift.

I had a chance to observe all the science on the vessel and talk to the crew about navigating on the open ocean.

Q: How was the weather?

A: In 10 days, we had a full range of weather conditions, from a raging storm where the 12-foot swell ran against the waves to millpond-like conditions. We also had fog where visibility dropped to less than 300 feet. We didn’t see land very often except when we entered Cape Cod Bay, and during a very rough time off Long Island, when the captain decided to duck behind Block Island for an evening so people could get some sleep.

Q: What do you think the impact is of this work on Rhode Island? On our broader understanding of this region?

A: One goal has been to understand the possible impact of wind development on marine life. These surveys have been used to implement where and where not to place wind turbines. The Bigelow also does fishing trawls, although not this trip, and those help set management guidelines for Northeast fisheries. Plankton is the base of the food chain and predictive of ocean productivity. Fish, birds and whales respond to those changes. Plankton biologists with knowledge of water chemistry changes can predict those changes.

Climate is changing – we see that in ocean acidification, how ocean acidification affects shell thickness in developing planktonic larvae, changes in temperature and salinity. Fish are changing their distributions; seabirds and whales follow the fish and zooplankton.

Q: What story do you think the data you collected will tell about what’s happening in the region?

A: Climate change impacts on fisheries are probably the most economically important to the region. Those concerned about wind turbine impacts on marine seabirds and whales, as I am, should recognize that NOAA has been involved in data collection long before the first wind turbine went in off Block Island, and that data is critical to the placement of future turbines. The potential impacts of the turbines on fisheries, whales and birds will continue to be monitored as long as their funding remains in place.

Q: Is there anything else you’d like to share about this trip or the project overall?

A: NOAA’s situation, like all nonmilitary government initiatives, is under extreme budgetary scrutiny. NOAA crew and scientists are dedicated to exploring and understanding the oceans – which make up the majority of the planet’s surface, drive our weather patterns, provide most of the world’s oxygen and, because of the food we derive from the ocean, support an important food web. The oceans are changing rapidly, and the fisheries resources are limited. The ocean is vast, and we know relatively little about it. NOAA crew and scientists are a key element in developing a sustainable relationship with our oceans.

During the 51.5 hours of counting seabirds and whales, I tallied 67 balloons (consider that one balloon for every 10 miles traveled, in any direction, across the entire ocean). Bringing it back to something tangible we can do to make a difference, we need to ban balloons on campus, in the Ocean State and perhaps from all coastal communities.

You can read the results of NOAA’s ongoing ECOMON surveys of the Northwest Atlantic here, and see more of Chace’s photos and videos from the research voyage here.