Dr. David C. Wilson previews his Salve MLK Week keynote

Racism and racial resentment aren’t the same. Understanding why can change how we talk about both race and democracy.

Salve Regina University’s tradition of honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s work continues in 2026 with a full week of events Jan. 25-30. From the Dream Brunch to a racial justice and nonviolence vigil, spoken word performance, Sabbath time, a Mercy Reading Club discussion and a day of service, we explore the impact, witness and call of Dr. King’s work on our community. The highlight of the week is the keynote lecture and dialogue session, this year presented by Dr. David C. Wilson, dean of the Goldman School of Public Policy and professor of public policy at the University of California, Berkeley.

Wilson gave us a preview of his talk “Testing Democracy: Racial Resentment in American Life and Politics,” to get attendees into the mindset for the session.

Q: Your research – and the topic of your keynote, is how racial resentment impacts American life and politics. What is racial resentment? Is it the same as racial prejudice?

A: They are not at all the same. Social scientists make distinctions between race-relevant phenomena like racism, prejudice and discrimination. Racism is fundamentally about one group’s superiority over another group simply due to group membership, and it assumes inequality and separation are acceptable. Racial prejudice is a faulty and inflexible generalization grounded in hatred; it is the feeling component tied to race. Discrimination is the behavior that results from attitudes, beliefs and judgments about others.

Alternatively, racial resentment is indignation over how race is used to attain a positive outcome that is not deserved. It is about justice and an appraisal of deservingness. In short, prejudice and racism have application to an individual or group, regardless of what they do, and resentment flows from one’s beliefs about another’s deservingness.

Resentment is the anger we feel when something we believe is wrong is being rewarded, and something we believe is right isn’t being rewarded. It’s important to acknowledge that resentment is inherent in humans. We all hold resentments. We sometimes resent our mates over perceived imbalances. Resentment is often fostered by myths that legitimize one’s feelings. For example, the idea that one’s mate is not trying hard enough in a relationship. Similarly, resentment becomes racialized through myths about other groups’ actions, such as “they are trying to skirt established rules and norms to gain advantages.”

Once we understand that resentment is universal, we can start to look at how it gets racialized. We have gotten sloppy thinking about race. We lump all of the thinking about race into “racism” or “prejudice.” The only reason some think of racial resentment as prejudice is because it is “racial” but that alone doesn’t make it prejudice or racism. That said, judgments about deservingness are definitely influenced by racism and prejudice, and resentment might produce racial prejudice and racism.

However, the judgment of deservingness itself is influenced by the need to believe justice exists (i.e., merit is the criteria for fair reward distribution) and resentment is reduced by restoring justice in one’s mind. In theory, actions don’t matter as much for prejudice and racism as they are group based.

To sum it up, resentment is not a form of prejudice; but rather, a reaction to a perceived way of understanding that society is, or our policies are, distributing rewards in unjust ways. If resentment is a form of prejudice, then nearly all other natural sentiments like envy, jealousy, pride, sadness and fear must be too, which means we are all prejudiced regardless of our actual status and power (e.g., oppressed populations). That does not seem consistent with the original thinking about prejudice.

Q: Why does the difference matter?

A: Racial resentment can result in the same outcomes as racism and prejudice, but that doesn’t mean they should be treated the same way. Similarly, political partisanship (Democrat/Republican) and political ideology (conservative/moderate/liberal) can produce the same outcomes, but they are not the same.

Confusing prejudice and resentment can get in the way of democracy’s progress. Resentment issues can be changed with information, treatment behaviors (e.g., counseling), common goal activities (e.g., problem-solving commissions) and restorative justice practices (e.g., commissions and dialogue sessions). Racial prejudice and racism flow from more ingrained beliefs that are hardwired over time. Our data show that resentment is grounded in beliefs tied to status threats, social change and meritocratic fairness rather than hatred or dislike related to one’s skin color.

Our study on racial enabling found three distinct groups that characterize attitudes toward race: self-identified racists, non-racists who oppose racism but don’t take action against it and anti-racists who actively work against racism. We found that racial resentment is most prevalent among non-racists who feel burdened by the need to confront racial issues and who resent being perceived as racists.

From my perspective, we know plenty about racists and racism. We need to know more about people who enable racism by not having a problem with others being racist and who are unwilling to do something to help others achieve equality. As America changes and concerns about why it’s changing continue (e.g., threats related to “othering”), resentment is only going to increase.

This is the place where we have opportunity to have conversations that go beyond labeling people as racists and address underlying issues effectively. Once we call someone racist, the opportunity for listening and agreement diminishes instantly. We can give people a new lens to think and talk about race and a new language that provides room for change. We can talk about why people are angry easier than we can talk about why someone dislikes another group.

Q: How does your work continue the legacy of justice that MLK was seeking?

A: My first job out of undergrad was working on the initiative to make Martin Luther King Jr. Day a federal holiday. I saw resentment by white Americans for the idea of a holiday granted on a perceived basis of race. I saw resentment by African Americans who perceived race was being used as a reason to not grant the holiday.

My goal as a scholar is to generate a deeper understanding of the continuing dilemma of racial justice and racial resentment. I hope people use my research to understand through data that racial issues aren’t just about hate and dislike. I hope to get people to want to learn about themselves, and to think about policies that lead to healing. Resentment is a cycle of blame, denial and avoidance. There are opportunities to address healing anger over fairness.

Q: As a community with justice at the heart of our mission, what kind of actions can we at Salve take to address racial resentment?

A: Two of the main takeaways from looking at the big picture around racial resentment are tolerance and forbearance.

I would offer that in a democracy, there are times when people need to be okay with discomfort. To be a social servant who cares about justice, you have to be okay with letting some things exist that might bother you. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do anything about it, but it should not fuel your anger. It’s okay to advocate, but if you wear it on your sleeve, it gives permission for others to wear their antagonisms as well. Tolerating others is critical for democracy and freedom, and it’s very difficult to change people and their beliefs.

Know that the system will produce injustices. Humans are prone to error. It’s difficult to squeeze the bad out of anyone or eliminate corruption entirely. Our task is to continue to fight for chances to make things better.

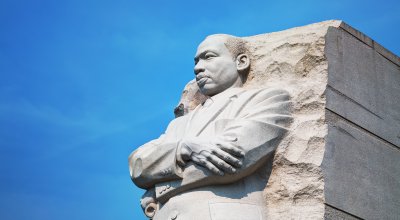

Featured image by Getty Images/AndreyKrav